CBG Pilot Results

Guides that meet teachers where they're at: what kind of impact did it have on instruction?

At Justice Rising, we piloted Chalkboard Guides for six months across grades 1-3 in our primary schools from January 2023. 18 teachers were given guides and introductory training, and 18 were not, and all 36 classrooms were observed to see what difference using Chalkboard Guides would make.

Chalkboard Guides are designed for use in protracted conflict and crisis settings, meant to withstand the challenges these settings present. Conflict and crisis have been ongoing since the prototyping phase: we tested the guides in a tent school (the original having been destroyed by a volcano eruption) and in schools that closed every Monday for ghost town due to conflict. The pilot took place against a backdrop of particularly intense rebel activity: 3 schools were displaced by rebel groups during the pilot; 2 others became host schools to displaced communities. Whilst the disruption stopped us from monitoring the pilot in the way we wanted to, it was an important reminder of why we designed Chalkboard Guides in the light-touch way that we did: one half-day introductory session and paper guides, without any follow up coaching, which is commonplace in structured pedagogy solutions, but would have been impossible once the rebels took control of key roads. The 18 teachers given Chalkboard Guides were not obliged to use them - we wanted to see if teachers wanted to use them on their own merit.

Why not make best-practice guides?

Chalkboard Guides are not best practice guides. Instead, they seek to meet teachers where they are:

with powerful tweaks (six key applications of cognitive load theory + one formative assessment application)

embedded into familiar pedagogical traditions

We took this approach from how we do teacher training: a network-wide application of leverage observations to identify one or two powerful tweaks to introduce at practice-based teacher training, reinforced throughout the year at a school and cluster level. These tweaks are embedded into existing, familiar pedagogy. Why? Because teaching habits are hard to change, and because where strong pedagogical traditions might be a powerful adversary, why not make them a friend?

In the Congolese case, pedagogical traditions offered:

Common pedagogical language in which to couch the introduction of powerful tweaks (connecting new learning to old for teachers themselves: for example, we could talk about the I do coming in the Activités Principales, and even more specifically in the Analyse).

Structures and strategies that could be tweaked, easily adapted, with applications of cognitive load theory (lessons traditionally begin with a Rappel (reminder) and end with an Application (opportunity for student practice)).

By doing this, we have found that we have been able to improve the quality of teaching and learning in Justice Rising classrooms, without disrupting the deeply held pedagogical mindset with which our teachers approach their work.

The key instructional strategies (tweaks) we embedded were:

Building on previous knowledge

Dual coding

I do, We do, You do

Leaving visual aids on the board

Clear and accurate worked examples

Sufficient independent practice

Formative assessment

So what kind of impact did embedding these have on adoption? To ask some broader questions, how much difference can guides that aim to tweak rather than overhaul instructional practice actually make? Does it mean a lowering of expectations? For anyone who has agonised over how to improve poor teaching practices, what can tweaking offer? Is it actually possible to respect and maintain existing pedagogical traditions and practices, and significantly improve teaching?

Observing instructional behaviour

We adapted the Stallings Classroom Observation System to detect for all but one of our key instructional strategies that we had embedded in the guides, and trained team members to conduct observations using Stallings uploaded onto Kobocollect. For building on previous knowledge, we weren’t able to sufficiently pin down what teacher and student behaviour should look like - homework for next time! If you’re unfamiliar with Stallings, enumerators take 10 equally spaced 15-second snapshots of a lesson and code what teachers and students are doing. We found that it yields a great overview of the lesson.

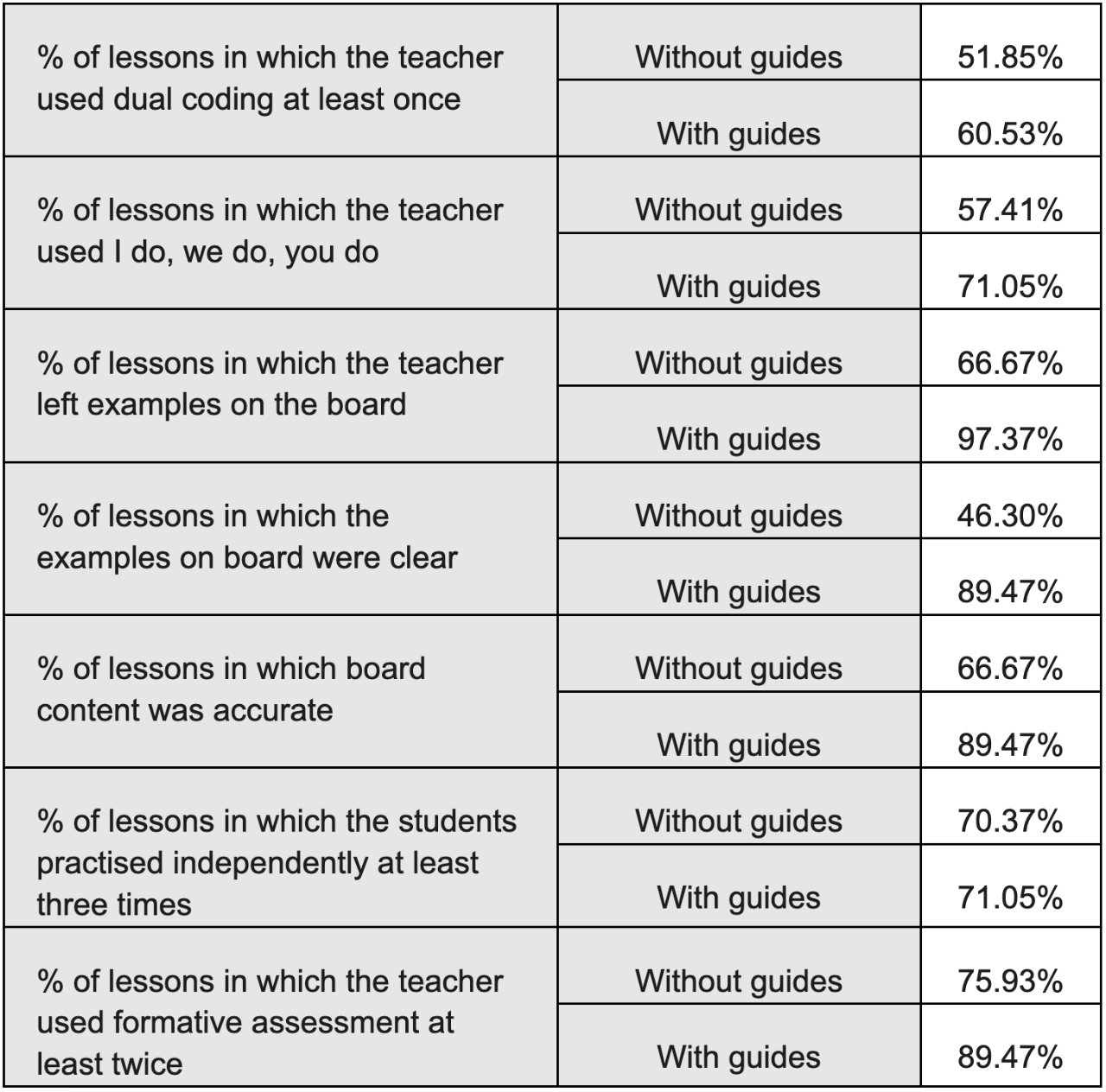

We wanted to get more rounds of data to look at changes in behaviour over time, but from the three rounds we were able to get out and collect, this is what we found.

Where Chalkboard Guides made the biggest difference was at the board: teachers left visual aids that students could refer to during practice, were a lot less likely to make mistakes on the board and laid board content out clearly.

Visual aids have been rubbed off the board.

Clear, accurate examples to refer to.

Where the board is the primary instructional tool used by teachers, this really matters, and was indeed one of the original concepts behind Chalkboard Guides. Context-specific repetition is one of the behavioural change mechanisms we built into the guides: where a classroom might qualify, we were even more specific, tying behavioural (instructional) changes to the board. It seems to have paid off.

We also saw teachers using formative assessment significantly more, circulating and checking students’ understanding during practice and providing individual support to struggling students. Teachers fed back that guides really supported weaker students; indeed, some teachers criticised the guides for favouring weaker students over stronger ones. But stronger students already achieve foundational learning. Chalkboard Guides purposely set out to provide visual aids for weaker students, and prompt teachers to provide individualised support for weaker students after identifying them in the We do and You do, and a consistent trend in the learning data is the gap reducing between the top and bottom.

Where we didn’t see a difference was in the amount of independent practice done. Whilst we would like to see that percentage rise (we’re already working on it), upon reflection, we also want to measure the quality of practice students are engaged in - something for us to go away and work on.

To return to some of our broader questions, we absolutely did not feel that we were lowering expectations: Chalkboard Guides supported teachers to adopt powerful instructional strategies. By offering tweaks embedded into familiar, traditional instruction, we tried to account for human behaviour, feelings and beliefs in the design of our intervention.

As one teacher said, “When I use the guides I feel at ease, because it has all the material that I need. I feel proud of what I’m going to teach!”

As for whether they improved teaching, yes, they did! Further adaptation is needed, but step into a lesson where a teacher is using Chalkboard Guides, and you don't have to look very closely to see the improvement. Moreover, teachers feel at ease using and talking about them: they have assimilated the rhetoric of our key instructional strategies into their pedagogical discourse:

“The most useful part of the guide is the “I do”, because when you explain the material well, it enables the “we do” and the application [you do].”

Looking ahead, we are really excited to begin a second pilot of Chalkboard Guides with Street Child in Cameroon, for which we are in production. This pilot gives us the opportunity to see what difference Chalkboard Guides can make in a larger sample of schools, from outside our network, as well as feeding forward some of the lessons learnt from the DRC. Will we succeed in embedding powerful tweaks in a different context, outside the schools we directly manage? Will Chalkboard Guides’ light-touch approach prove resilient amidst a different conflict? We are getting ready to find out!