What kind of schooling do students in protracted conflict and crisis need?

Our schools have faced various crises in the last six years: Ebola, COVID-19, the eruption of Mt Nyiragongo, and small and large-scale rebel group movements. These events occur without warning or sequence, often compounding upon one another. The effects? They cause anything from two-day closures to whole-school displacement to co-existence within rebel-held territories to tent-schooling.

Over these six years, we have more than doubled the size of the school network, and despite schools having every reason to struggle, we’ve seen school after school successfully establish themselves within their respective communities and authorities. Despite being led by new-to-the-job school leaders, these schools consistently grow enrolment (with gender parity across the network) and fee collection, and deliver near 100% pass rates at the end of primary school exit exams.

It’s made us think long and hard about what we’ve learned as a school network operator amidst protracted crisis and conflict, contemplating questions such as: what’s working, why is it working, and how? With guidance and support from the Global Development Incubator, we’ve been drawing the lessons learned, alongside what the available academic literature has to offer, into a framework for quality schooling in protracted conflict and crisis settings that we can use to reach students – every student – in protracted conflict or crisis.

The problem is vast. 152 million children attend school in a protracted conflict setting globally and 127 million of these children have poor learning outcomes. Students in sub-Saharan Africa who attend school in conflict settings typically learn six times slower than even their peers who are experiencing other types of crises.

Why focus on schooling?

It’s quite simple, really. Schools are the main vehicle of education and they are everywhere, even amidst conflict and crisis (at 50). Schooling is always being enhanced, but is highly unlikely to be replaced. Moreover, although we’ve seen that schooling doesn’t always = quality learning, the reverse is also true: quality learning doesn’t always = quality schooling. This matters, because schools have a duty of care towards the children enrolled there. However, quality schooling will always deliver quality learning, and more besides!

What does quality schooling look like?

A new headteacher leads structured play during recess in the DRC

At Justice Rising we've been talking about the kinds of schools students in protracted conflict and crisis need to attend, to learn all they need to build the life they want. If we fix learning as the primary outcome of schooling, what else is needed to ensure that students are set up for success?

We've looked at the available literature for that, while also asking ourselves, our team and our stakeholders: what makes our own schools successful?

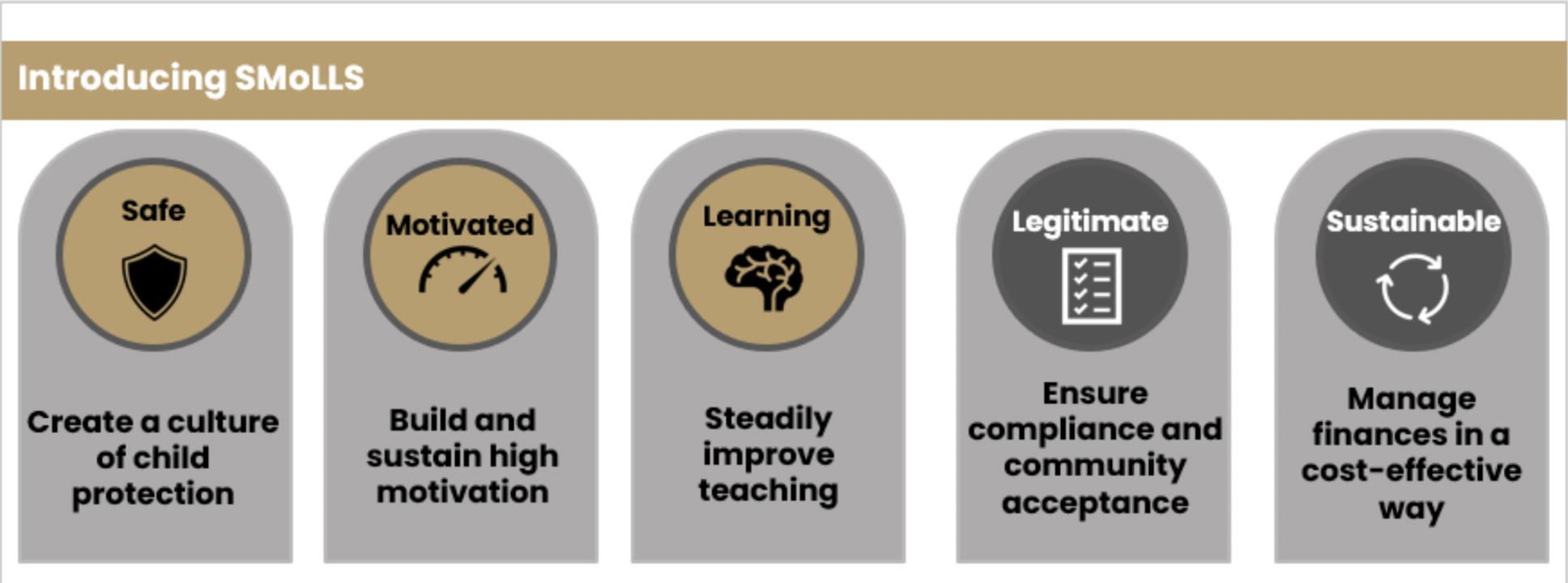

Here’s where we landed: Children need to be Safe, Motivated and Learning in schools that are Legitimate and Sustainable. This makes up SMoLLS (or SMoLL Steps, which we'll introduce in a later blog) – the five overarching and mutually enabling domains of our quality schooling framework.

For safety, child protection needs to go beyond compliance to become culture (at 42) - the way we do things around here. So from the way children enter school grounds, to how break times are supervised, to assemblies and what happens when a child misbehaves, the adults at school must set up systems and behave in ways that protect children and childhood.

Motivation is important in any setting but even more so in conflict zones, because the sheer scale of challenge to be worked around or overcome is much bigger. Here, we focus on consistently motivating teachers (at 11) so that they can motivate students.

Learning is central because that's what children come to school for and a major factor in why students drop out of school (at 29-30). It needs to happen at pace, require only a few, key resources and deliver what students and their parents see as meaningful qualifications (at 12) that they can use to build the life they want. That usually means, especially in these oft-hard-to-reach settings, that the headteachers need to be the ones who support teachers to improve.

Legitimacy comes from community acceptance as well compliance with the relevant authorities (military, government, NGO clusters, even rebel groups where there is coexistence). The former, because community acceptance usually brings community protection (at 44) as students and teachers walk to and from school. The latter, because they can, at a whim, shut down operations.

Sustainability means a 3-5 year journey of supporting schools with fee collection and diversifying income streams (at 28) (where needed) and helping them to prioritize spending so their budgets are used in a cost-effective way.

Delivering “a good day at school”, everyday.

“How was school today?”

Millions of students are asked this question everyday. Their answer can be influenced by any combination of the myriad of stakeholders and components that influence that day at school: from the school leader’s mood at assembly, to who they were sat next to in class, to their latest test scores, to a lesson that left them feeling confused and doubting their ability. At Justice Rising, we believe that being safe, motivated and learning in schools that are legitimate and sustainable are what make for the best days at school, and that students need to access a “good day at school”, everyday, in order to learn everything they need to build the life they want. With SMoLL Steps, we are setting about reaching every student in protracted conflict and crisis with the kind of schooling that transforms war zones. What steps can you take to join our journey?

In our next blog, we'll dive into SMoLL Steps, give some examples, and explain our design thinking behind them. If you want to get in touch with us about SMoLLS, please email ee-reh.owo@justicerising.org.